Winner, 2024 John Whitney Hall Prize by the Association for Asian Studies “for an outstanding English language book published on Japan during 2022.”

Finalist, 2024 Modern Japan History Association Book Prize

Finalist, Association of American Publishers 2023 PROSE Award in “World History” Category.

Sherzod’s book, Eleven Winters of Discontent: The Siberian Internment and the Making of a New Japan was published by Harvard University Press in January 2022.

Eleven Winters of Discontent is the first comprehensive history of the Siberian Internment in English based on Japanese, Russian, and English-language sources. Unlike most of the scholarship published on the internment (very little of it in English), the book relates the Japanese prisoners’ Siberian odyssey as a transnational event not limited to national borders and histories, a chapter of tremendous complexity that should be studied through international, multilingual sources.

Praise for Eleven Winters of Discontent

“The Siberian Internment is one of the forgotten episodes of the Second World War. In this fascinating account, Muminov exploits Japanese memoirs and Russian archives to tell a complex history, attentive both to individual lived experiences and to structural change, including the waning of the Japanese empire and the emergence of the Cold War. A stimulating challenge to the traditional boundaries of Japanese history!”

Sebastian Conrad, author of What Is Global History?

—

“This magnificent work is the first transnational and comprehensive treatment of more than 600,000 Japanese POWs captured in Northeast Asia who were transported to forced labor camps in the Soviet Union, where they languished for many years before a fraught repatriation to Japan. Muminov depicts the POWs with sympathy and compassion, yet examines the history with detachment and objectivity. Eleven Winters of Discontent offers impeccable scholarship, forceful argument, and a gripping narrative.”

Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, author of Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan

—

“A fresh, new history of the Siberian Internment that goes beyond hackneyed narratives of victimhood. Using a contextually broader and chronologically longer framework, Muminov moves the internment history beyond a national Japanese experience to a larger transnational story shared by various foreign POWs. At the same time, he reminds us how postwar Japan carefully erased the imperial past by remembering a particular set of hardship narratives while averting its eyes from anything that recalled the empire. An outstanding contribution to our reconsideration of the early postwar and Cold War world.”

Masuda Hajimu, author of Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World

—

“Muminov renders much-needed complexity and diversity to existing nation-centric narratives of the Siberian internment of over 600,000 Japanese. Giving agency to both Russians and Japanese on the ground, he offers transnational perspectives long called for but rarely achieved. This is a nuanced yet comprehensive treatment of the internment and its sociopolitical life in postwar Japan as well as a riveting read for anyone interested in the global history of war and the making of a postwar nation state.”

Sho Konishi, author of Anarchist Modernity: Cooperatism and Japanese–Russian Intellectual Relations in Modern Japan

What was the Siberian Internment?

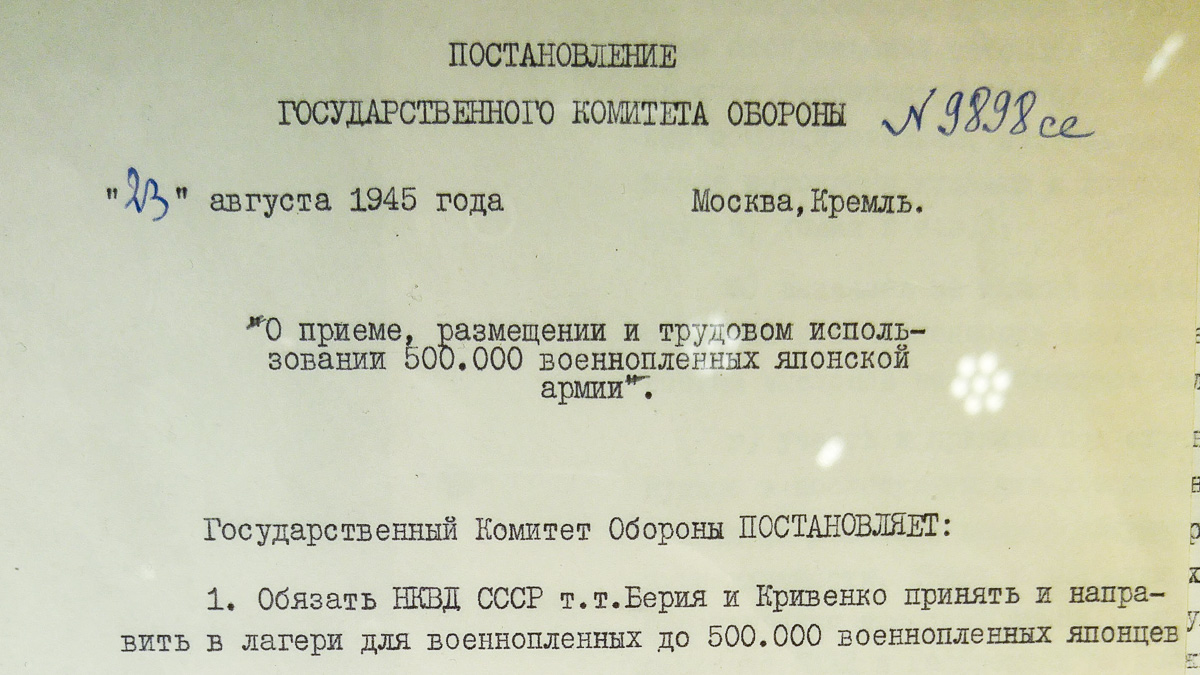

The Siberian Internment started with the capture of over 600,000 Japanese former servicemen by the Soviet Red Army in northeast Asia in August 1945. On the 23rd of that month, Joseph Stalin signed a secret order “On the Reception, Accommodation and Labour Exploitation of 500,000 Prisoners-of-War of the Japanese Army” (please see a copy of the document in the below image).

In one of the largest forced migrations of the past century, the Soviets rounded up those Japanese deemed “fit to work in the conditions of the Far East and Siberia”, assured them they were being sent home, and deported them to the USSR in freight trains. Interned in labor and prison camps across the vast Soviet landmass for periods between a few months to eleven years, the Japanese were exploited for labor and indoctrinated in the main tenets of communism. About a tenth of their total died in the USSR, succumbing to cold, malnutrition and backbreaking work; almost all of the survivors were released by 1950, barring a few thousand “war criminals” convicted of “anti-Soviet” crimes and often transferred from camps to prisons. The last group returned to Japan on December 26, 1956, two months after the restoration of diplomatic relations between the USSR and Japan.

Amidst hunger, abuse and deprivation of their illegal captivity in enemy hands, each Japanese prisoner cherished the dream of returning home. Few could be sure they would be able to once again walk the streets of their hometowns, or taste the rice cakes made by their mothers. Yet the internees’ travails hardly ended with their return home; in the US-occupied Japan many of them were greeted with suspicion and had to grapple with unemployment and discrimination in the increasingly anticommunist society. Through their association with the USSR, many became drawn into the early Cold War ideological battles, seen by their compatriots as unique witnesses and alleged agents of the Soviet enemy. For decades thereafter, thousands of them engaged in a Sisyphean struggle for recognition and compensation against successive governments.

Eleven Winters of Discontent retraces the internees’ voyage through Siberian camps, where each station unfolds a new layer of knowledge about the place and the historical period: Japan’s puppet-kingdom of Manchukuo on the eve of defeat, freight trains and transit camps on the road to the USSR, barracks and camp infirmaries, work sites and leisure centers, classrooms and propaganda program reading clubs, repatriation ship decks, train stations, homes, assembly halls and streets of postwar Japan. In reconstructing each point in the peregrinations, the volume draws on an eclectic mix of hitherto little used sources from the period: Soviet archives, Japanese memoirs and government documents, author’s interviews with the survivors, POW postcards sent from Siberia to Japan, US Occupation reports, newspaper and magazine articles, photographs, camp maps, films, paintings and propaganda leaflets. Above all, the book illustrates the complexity of the internment and the diversity of captive experiences in both the camps and in postwar, Cold War Japan.